|

The

adventures of John Storm and the

Elizabeth

Swann. John Storm is an ocean

adventurer and conservationist. The Elizabeth Swann is a fast solar

powered boat. During a race around the world, news of the sinking of a

pirate whaling ship reaches John Storm and his mate Dan

Hook. They

decide to abandon the race and try and save the whale.

(Original

Chapter 8) – Whale Sanctuary - 200

N, 1600 W (Aleutian Islands)

BAT

CAVE <<<

The Arctic region is a vast region of icy seas and snow covered lands where the sun does not set in summer, nor rise in winter. This desolate expanse is home to hardy Eskimos, a race of superbly adapted nomadic aboriginal flesh eaters, polar bears and seals. Around the North Pole, the waters are permanent sheet or pack ice. Further south, the ice melts in summer, which melt is gradually creeping north as the earth is warming. In winter Eskimos shelter in igloos, in summer in animal skin tents. They live on a mixture of fish, seals and the occasional whale, when meat is plentiful. Their clothes are fashioned from furs and they are skilled artisans.

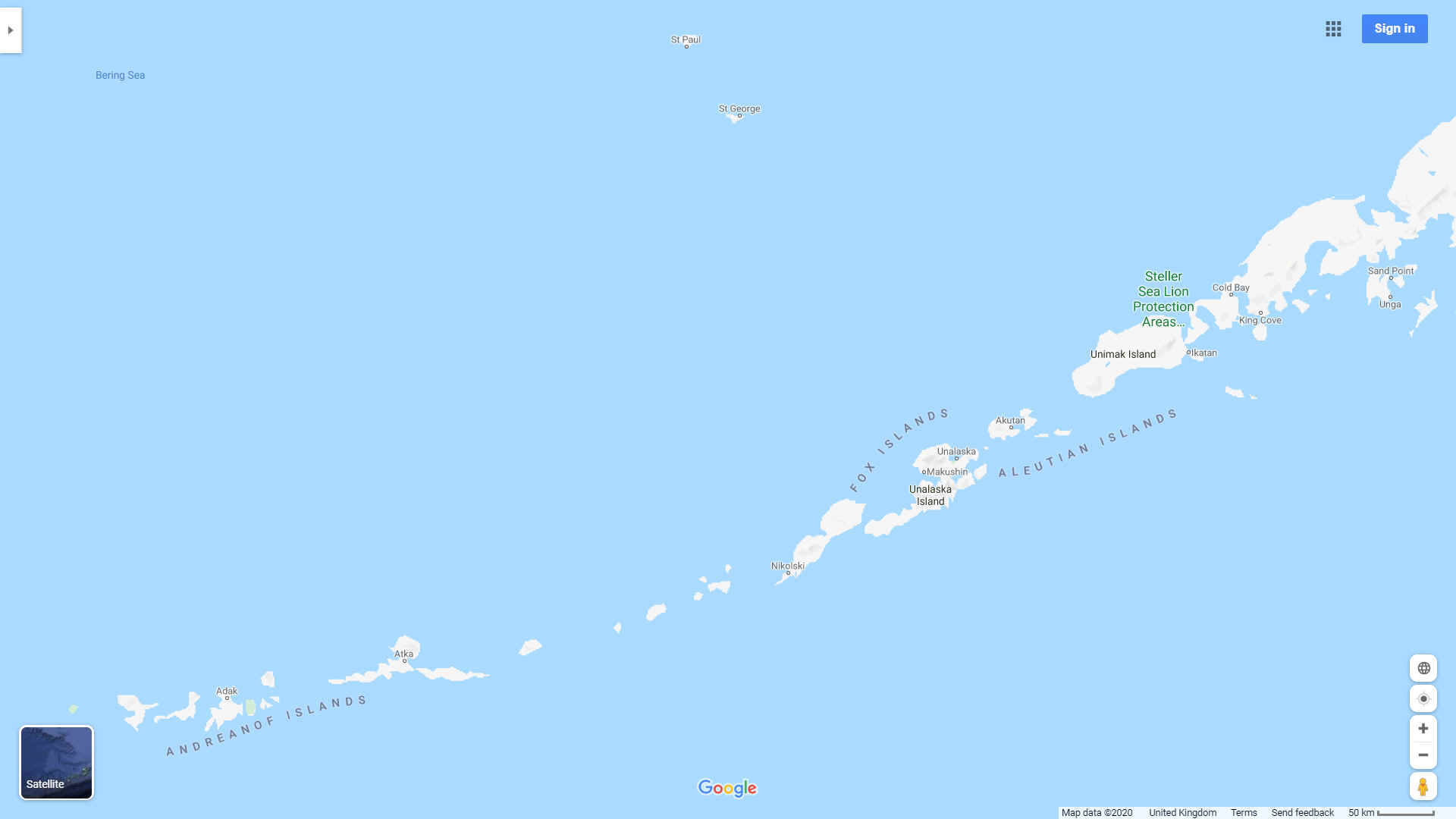

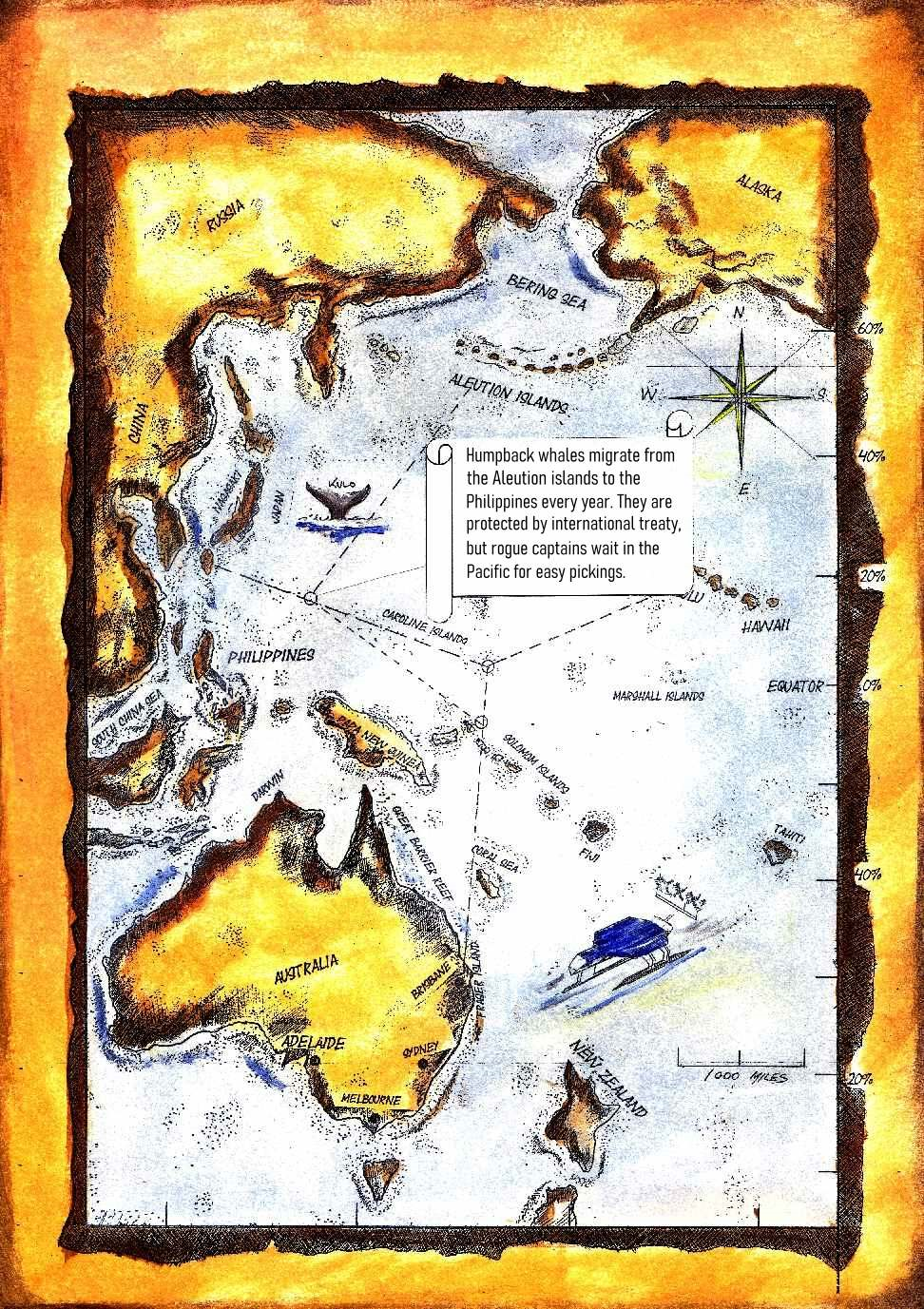

Further south at the rim of the Bering

Sea, the Aleutian Islands are the feeding grounds for the humpback whale, giant rorqual acrobats and accomplished vocalists. Humpback whales have strange white patch splashes on their unusually large front flippers and body undersides, presumably as camouflage. The flippers are roughly a third of body length and irregular shaped with round knob like projections on their large upper and lower jaws, and long head. Humpbacks are fond of leaping out of the water in a display called broaching, when their deeply notched tail flukes are a distinguishing feature.

Humpbacks have widely spaced throat grooves that expand in billows fashion to allow them to intake large volumes of water. They have no teeth, but feed by filling their mouths with water containing zooplankton, krill and fish, then filtering out the water, expelling it through flexible baleen strips made of keratin, a strong fingernail like substance, which hang in closely packed rows, curtain fashion from the upper jaw. The small animals trapped in their mouths by this sieving process are then swallowed. Groups of Humpbacks hunt in teams, swimming in circles around a fish shoal making bait balls in a technique known as bubble net feeding. A dozen or so whales work together to harvest the bonanza of shoals. This requires a high degree of intelligence, good timing and communication; the water equivalent of pack hunting.

The lead whale dives first and locates a shoal, then swims around it in a circle releasing air bubbles to create a theoretical spiral curtain. The other whales join the leader from underneath in a tight formation, singing to confuse the fish. The fish are then panicked to swim ahead reluctant to enter the bubble curtain barrier, so swim upwards, followed by the whales who all surface mouths agape to net a concentrated fish mouthful. Using this method the whales can easily take a ton of fish a day.

Humpback whales can vocalise for up to thirty minutes at a time. Each song is complicated and unique when compared to songs from other whales in their group. Clearly, singing is a means of communication. They are the longest most complex sound sequences of any animal, save for the vocalisations performed by humans supported by orchestras in operas. These songs can be heard many miles away and each regional population has its own song, sung only during the breeding season. To sing, the whale vibrates air inside itself, in a chamber of bone, but how they achieve this is a mystery, since they have no vocal chords. The bone chamber appears to be a natural harmonic wind instrument.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle recognised that whales breathed air and bore live young as far back as 310BC. Cetaceans are divided into two suborders: Odontceti (toothed) and Mysticeti (baleen) whales, with two blowholes on top of their heads. There are 12 baleen species divided into 4 families. Humpbacks are rorqual whales belonging to the ‘balaenopteridae’ family. Mothers are protective of calves which they suckle for 10-11 months weaning at about 12 months. The calves reach maturity at around 5 years. They can weigh up to 45 tonnes and grow up to 19 metres in length. Kulo is considerably heavier, a veritable giant weighing nearly 60 tons. Female Humpbacks typically breed every 2-3 years.

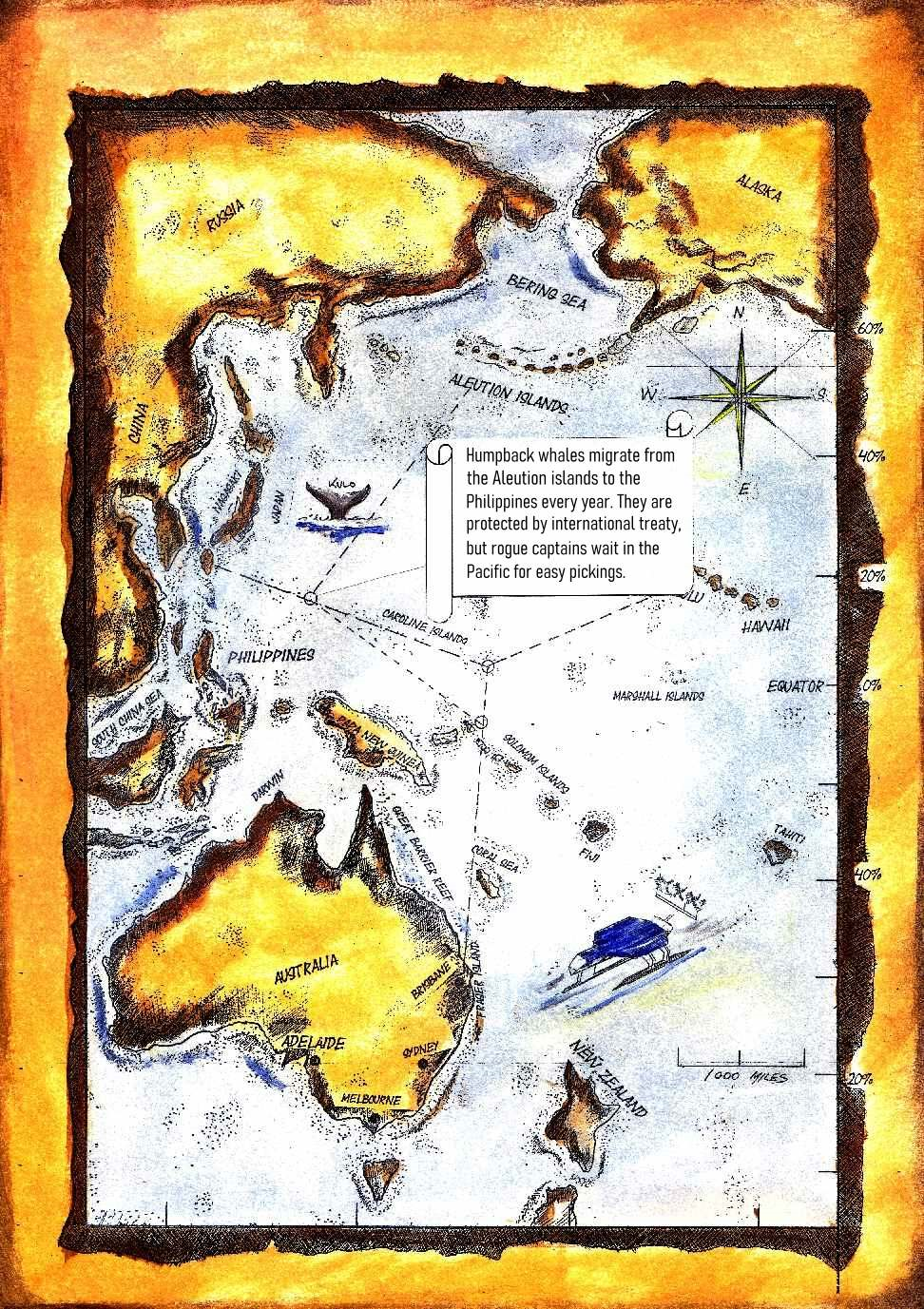

It was early in the fall and the beginning of the annual migration from the Gulf of Alaska to the Philippines. One group of North

Pacific humpback whales had already started the 3,500 kilometre journey to warmer waters, a grand summer migration, to complete the reproduction cycle; and a very necessary adventure to allow calves to be born in more comfortable surroundings. Migrations are thought to have developed when the food whales fed on moved to cooler waters as changes in continental drifts and ocean currents took place. whales simply followed the food supply as they moved to polar regions, but habitually returned to warmer sheltered waters to provide a suitable environment to give birth.

Their migrations often extend to 16 to 20,000 kilometres in total in a year, so this is just one small leg of their journey. The young and mature males were always the first to leave the group, eager to mark their territory. The adult females joined in, as a trickle herd, out to stretch their muscles after many months of gorging in the rich feeding grounds that are the trademark of the northern waters. Many land mammals and birds, make long treks to reach seasonal feeding grounds, but these treks are dwarfed by the vast annual journeys made by whales.

The last to leave, is the giant female named Kulo, shadowing her young female friend called

Kana. These two whales had been identified and tagged by SPLASH project volunteers (Structure of Populations, Levels of Abundance and Status of Humpbacks). Their names had been given to them after deciphering of their grunts and singing, by a computer sampler linked to a hydrophone. Kulo and Kana had become great friends despite their disparity in size. Kulo was by far the largest whale in the group and a gentle giant, even bigger than her male counterparts. She is very strong and confident and well respected because she is also clever. She has a temper, which very occasionally snaps; then watch out. Many a male humpback taking liberties had been chased, caught and bruised for their troubles. If a human, she’d have been a redhead, Maureen O’Hara.

Kana, is the smallest and youngest of the group, so a slow swimmer, but intent on meeting her sisters at the other end of the migration route. The epic exodus normally lasts from 4 to 8 weeks, depending on the rate of swim and currents. Kulo was in no particular hurry as she set a southerly bearing for the Babuyan Islands, just north of Luzon, in the Philippines. Although of course, she did no know the Island’s name, nor the compass bearing. She just knew the Island by its taste, warm clear, sheltered waters and the feeling of well being when she reached that location.

Humpback whales navigate by sensing Earth’s geomagnetic field. The tissues around their brains contain an iron oxide concentration called magnetite, allowing them to sense gradients. There are many different groups of whales in three populations spread about the globe, each with their own familiar pattern and customs. Some are North Atlantic and others cruise the Southern Hemisphere. Kulo and Kana are from a northern Pacific

pod, by far the biggest group of whales, making up approximately 60% of the world’s humpback whale population.

Kulo has eaten her fair share of schooling fish and krill and packed it all away in nature’s larder as blubber, which stores and releases energy on demand to sustain these wonderful animals on their travels. As she swam along she thought of all those long summer days chasing and being chased by the adult males, in a ritual as old as time itself, but none the less enjoyable for that. All the while the sun shone, providing the energy for photosynthesis, the basis of nearly all life on earth. This chemical reaction makes the algae bloom aplenty as they manufacture carbohydrates, which in turn provides food for the next in line in the food chain.

Humpback adults can eat up to 2,000 pounds of krill in a single day. Every food chain eventually comes to a halt with the dominant animal it supports, in this case the humpback. Food chains as with any other form of energy conversion are dreadfully inefficient when viewed clinically. When man broke the back of the food chain by growing his own crops, on which to rely, he accidentally improved the efficiency of the supply chain and gave humans a huge advantage over other species. The invention of cooking, further improved the digestive conversion ratio, then man farmed animals intensively, since he had the crops to feed them and control of the environment, to include controlling his meat supply.

But that didn’t matter to our friendly whales. What mattered was when man became master of the oceans and greedy for energy. Whole towns were built up specifically to hunt for whales and the precious oils they could provide. This was before the discovery of petroleum in vast subterranean lakes, fractional distillation and the invention of the motor car. A large whale could be reduced to around 100 barrels of oil at about 10 barrels to the ton, plus other exotic compounds used as perfumes and lubricants, such as ambergris. The oil in the head of the Sperm Whale has such fine lubricating qualities, that only up until recently did NASA use it for their space programme.

At first the herds of these giant gray animals must have seemed an inexhaustible bonanza. But just as with the Bison of North America, slowly but steadily the population dwindled, until many species were on the verge of extinction. For this reason laws were introduced banning whaling, to prevent extinction. The International Whaling Commission was established in 1946 to conserve what stocks remained. An indefinite moratorium on all commercial whaling was imposed in 1982. The Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, prohibits trade in whale products, formerly used extensively in cosmetics and for ornamental carvings. The measures which are now taken to protect whales, has seen a revival of numbers, but the population is still only about a fifth of the pre-whaling days.

Where the people of Iceland, Japan and China traditionally included whale meat in their diet, the whaling ban has hit them hard. Eskimos still hunt whales in limited fashion, but they are not an industrialised nation, thus the impact on whale stocks is negligible. Very occasionally, Iceland has taken a few whales to a strict quota, but Japan operates large mechanised whaling ships, claiming that whales taken are for scientific research, which many authorities allege, due to the numbers, is in defiance of international treaties. For this reason fisheries protection agencies shadow such ships, to ensure there is no refueling at sea, which is prohibited to in some measure limit hunting locations.

Purpose designed whaling ships are more readily detectable by their size and shadowed by fisheries authorities and animal rights protection groups. Smaller privately owned fishing vessels are not so easy to keep track of, since they may be general purpose boats, converted from trawlers or other working ships. These opportunistic brigands are more dangerous to Kulo and her group, as they mingle with other marine transport. Advances in marine electronics, such as echo location fish finders and other sonar devices, makes the job of trawler captains that much easier. The problem though for modern whalers, is oddly enough, not one that the

Captain Ahabs of yesteryear faced. It is the price of fuel and range limitations of the modern diesel engine powered boat.

Kulo is not thinking of any of these issues which affect the survival of her species. She is happy to be watching her friend Kana stretching her flippers, rising and leaping from the sea and falling back amid a wave of silver froth and slapping her tail flukes, which is a sign of whale happiness. Kulo is thinking of meeting up with her mate Buka, himself a bigger than normal male humpback, who courted her for most of the winter, until finally they had a meeting of minds.

PIRATES

>>>

|

SCENE

|

DESCRIPTION

|

LOCATION

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prologue

|

Shard

Protest

|

51° 30' N, 0° 7' 5.1312''

W

|

|

Chapter

1

|

Arctic

Melt

|

580

W, 750 N

|

|

Chapter

4

|

Sydney

Australia

|

330

S, 1510 E

|

|

Chapter

6

|

Bat

Cave

|

330

20’S, 1520 E

|

|

Chapter

8

|

Whale

Sanctuary

|

200

N, 1600 W

|

|

Chapter

10

|

Pirates

|

330

N, 1290 E

|

|

Chapter

13

|

Solar

Race

|

200

N, 1600 W

|

|

Chapter

14

|

Darwin

to Adelaide

|

130

S, 1310 E – 350 S, 1380 E

|

|

Chapter

15

|

Six

Pack

|

200

N, 1600 W

|

|

Chapter

16

|

Whaling

Chase

|

240

N, 1410 E

|

|

Chapter

20

|

Empty

Ocean

|

200

N, 1600 E (middle of Pacific)

|

|

Chapter

24

|

Billion

Dollar Whale

|

250

N, 1250 E

|

|

Chapter

26

|

Rash

Move

|

140

N, 1800 E

|

|

Chapter

27

|

Off

Course

|

150

N, 1550 E

|

|

Chapter

28

|

Shark

Attack

|

100

N, 1650 E

|

|

Chapter

29

|

Sick

Whale

|

100

N, 1650 E

|

|

Chapter

30

|

Medical

SOS

|

100

N, 1650

E

|

|

Chapter

31

|

Whale

Nurse

|

100

N, 1650 E

|

|

Chapter

33

|

Storm

Clouds

|

150

S, 1550 E

|

|

Chapter

34

|

The

Coral Sea

|

150

S, 1570 E

|

|

Chapter

36

|

Plastic

Island

|

20

S, 1600 E

|

|

Chapter

39

|

Media

Hounds

|

170

S, 1780E

|

|

Chapter

40

|

Breach

of Contract

|

200

S, 1520 E

|

|

Chapter

42

|

Fraser

Island

|

250

S, 1530 E

|

|

Chapter

43

|

Congratulations

|

250

S, 1530 E

|

GRAPHIC

NOVEL

The

graphic novel

translation omits

many of the above chapters (in grey) entirely, and condenses others, aiming for a lively visual read.

This

story is a modern Moby

Dick, the twist being that there is a happy ending for everyone

involved with the $Billion

Dollar Whale, even the whalers. Herman

Melville would have approved.

Please use our

A-Z INDEX to

navigate this site

|